After The Deluge

The Museum of The Anthropocene Welcomes you. This exhibition shows life in the period following the Deluge Climate collapse and great extinction, in the years 0-1500 P.D.

The Museum of The Anthropocene welcomes you. This exhibition shows life in the period following the Deluge Climate collapse and great extinction, in the years 0-1500 P.D.

click left and right to scroll through more images, and scroll to the bottom for a note from the curator.

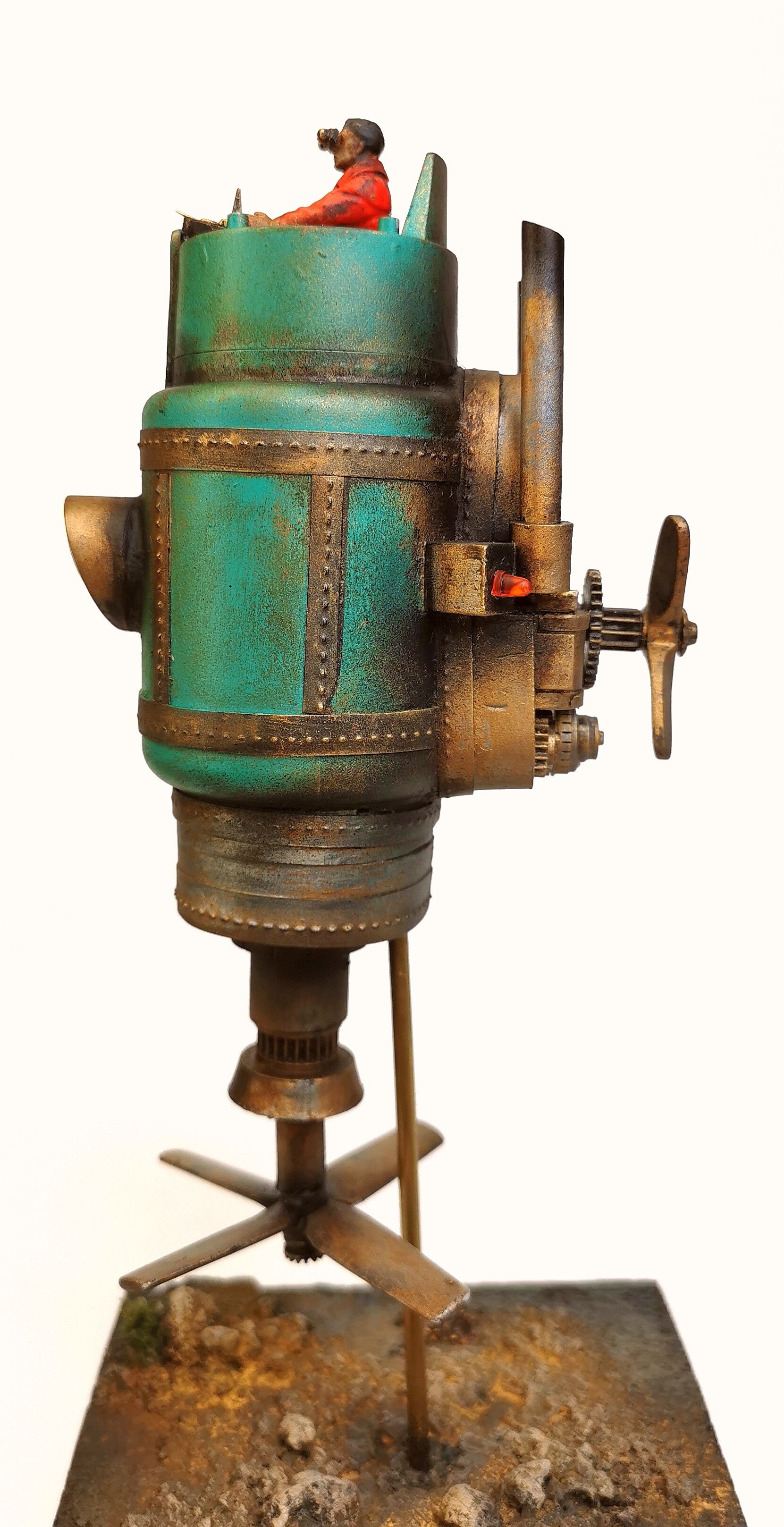

mobile mechanical engineering tender, circa 400-600 P.D.

Exhibit 14 shows an engineer's tender, which originally would have been for ferrying cargo short distances between a dock and a larger vessel, or between two vessels. The engineer who owned this vessel used the deck as a pickup for engineering projects, delivering larger parts like generators, or using it as he is here, as a mobile workshop. Engineers and those able to ferry parts were a key part in Post Deluge Society.

HAZARDOUS ENVIRONMENT VEHICLE, CIRCA 720 - 900 P.D.

Exhibit 6 shows a single occupant hazardous environment vehicle, with many life support systems crammed into the smallest possible space. In case of an emergency evacuation, if the canopy was unable to lift up and out of the way, the pilot would have to slide back the foot platform in order to squeeze down to the evacuation hatch. This was fitted with explosive bolts for rapid exit. The fully enclosed canopy could support the pilot for many hours at a time in or around hazardous conditions.

This vehicle was used for visual inspections of vehicles and cargo. The large canopy allowed a wide view with a panoramic heads up display to record and send information. Using vehicles like these, a merchant co-op could keep easy tabs and physical presence in their particular field, helping to control their area in whatever conditions. The rear canopy helped protect the powerful motor and kit, the vehicle was designed to be small enough to manoeuvre between docked ships, and to land easily on their deck, or inside a cargo hold. They were also key for early salvage operations, researching and scouting.

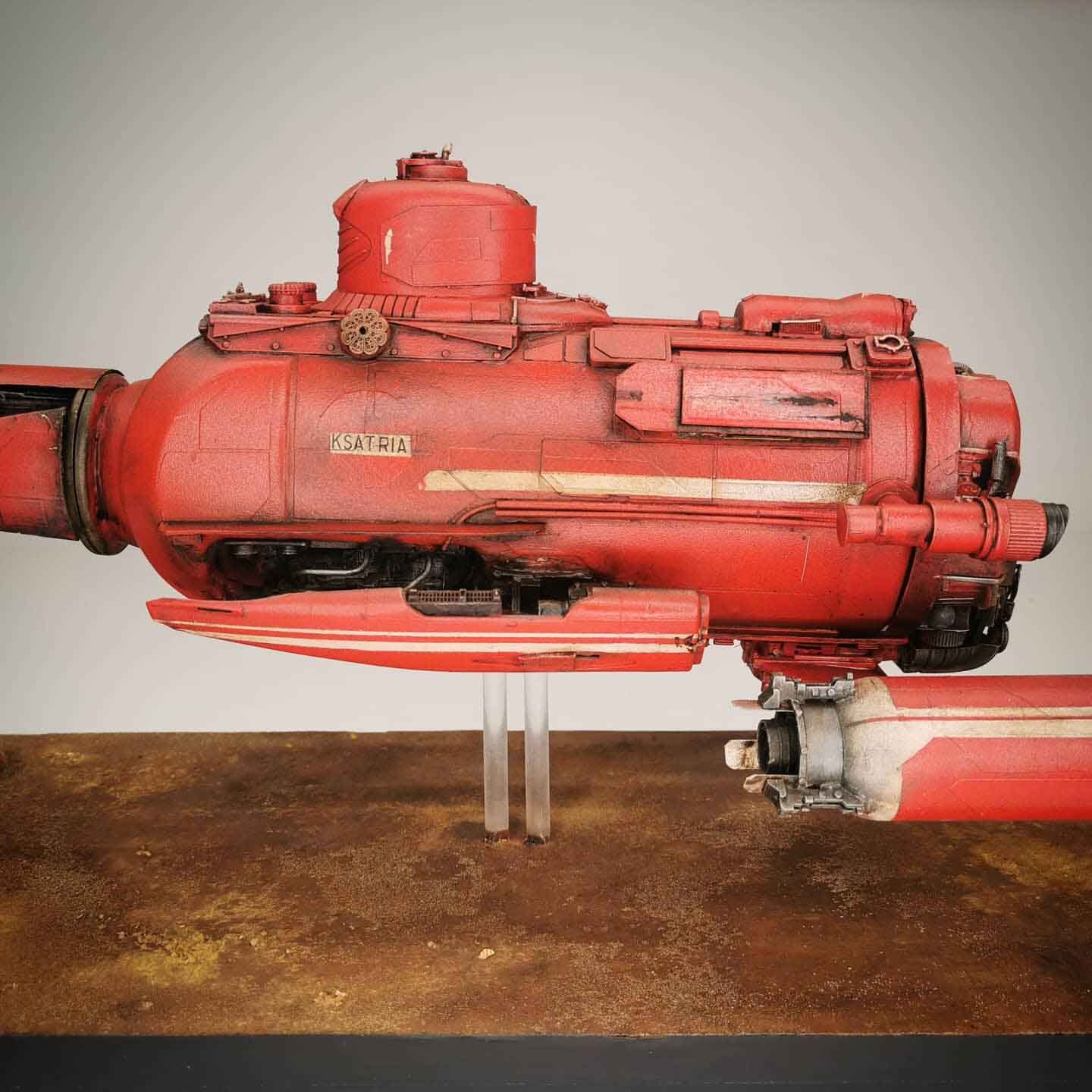

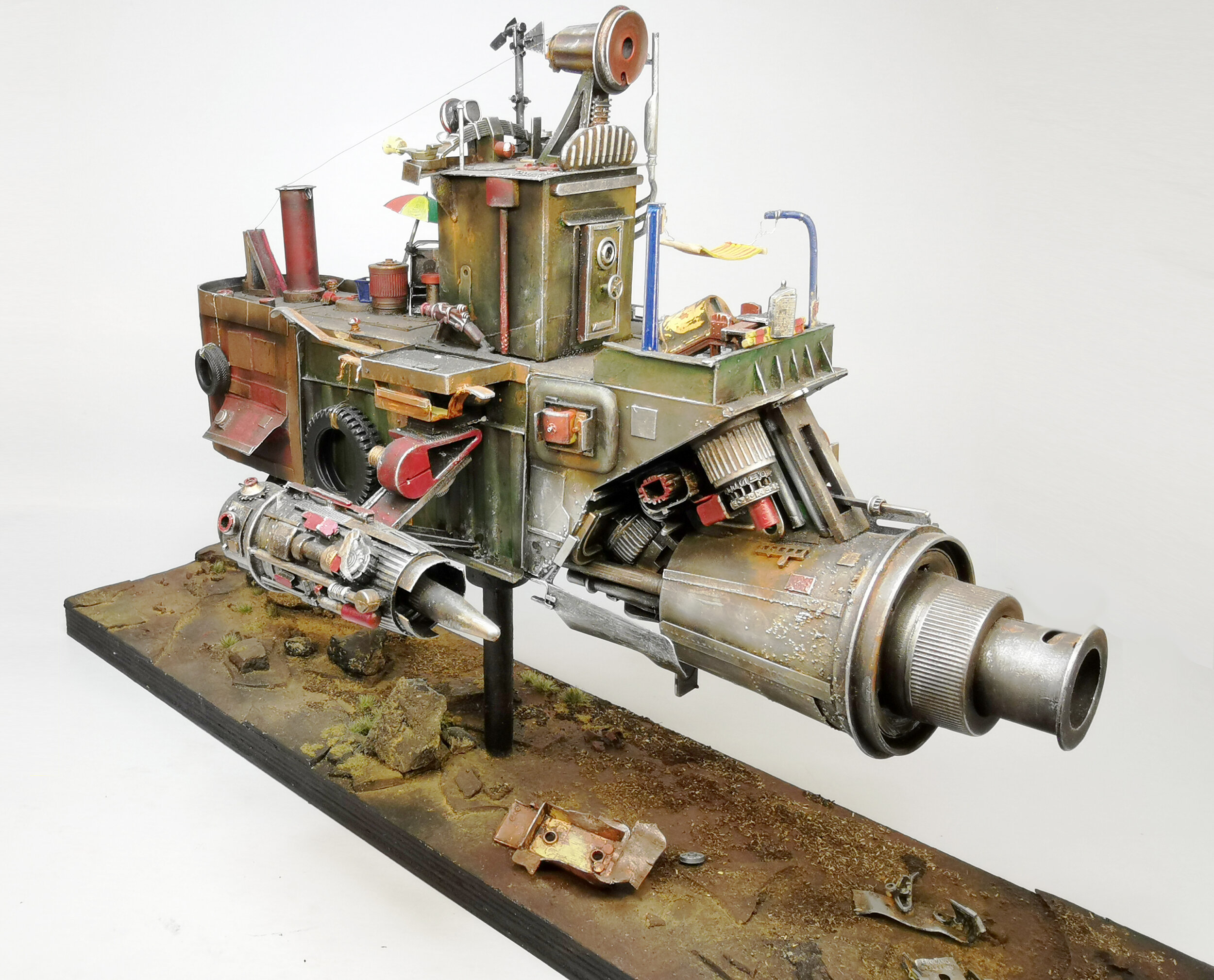

KSATRIA GROUP VEHICLE

????-1530 P.D.

Origin: unknown

Purpose: unknown

Exhibit 636 shows a maquette of a Ksatria Group Vehicle, the only specimen found, though many more are believed to have existed. The remains of this vehicle were discovered in the far north of the Goss Peninsula in 1531PD. Though little remained of the vehicle, and every piece of identification or onboard computing had been thoroughly stripped, the Museum of the Anthropocene has been able to reconstruct what it may have looked like.

Stories of the Ksatria Group have existed since as far back as Post Deluge records go, though there is some debate to their power or even existence. While it is certainly true that groups that controlled local labour and materials existed, the Ksatria Group's purpose and power has been either heavily overstated, or the group was better than anyone might have supposed at hiding their true scope of influence. Indeed there are those who believe even today that the Ksatria Group still exists as a shadow organisation, though this has been widely debunked.

What we do know is this vessel was built for strength and speed. It would have been highly manoeuvrable, incredibly fast, and was armed with enough firepower to put up a strong fight. The armour would have kept the occupants well defended, and though cramped, study of the Goss Peninsula wreck indicates there would have been enough space for a crew of three or four plus a small cargo hold for a modest volume of cargo, or perhaps, people.

Museum of the Anthropocene, 1898PD

n.b. Please do not write to me with any more suppositions about this exhibit. I have enough to get on with in the museum without reading some conspiracy theory nonsense.

The Curator

SILKY'S DESERT RACER, 900-950 P.D.

no one knows who Silky was, but we do know they lived somewhere 3-400 years after The Deluge. What scant information we have is largely in thanks to Silky’s own business: they were a data merchant. Silky (the name was a later nickname, attributed to their swift movements and ability to evade capture) travelled far and wide exploring the abandoned plains and former cities, searching out only for recoverable data. The remaining centres of learning, such as they were, relied on people like silky to harvest any data they could find on a variety of devices and would take everything they could back with them to sell on for a price. The economy of historical and scientific research relied on this, as post deluge, vast quantities of information was lost forever. The price for this was not just value however - Silky and other data merchants forced the economy of their data by getting as much as they could quickly and selling it for a high price - if they could not get a sale, they would threaten permanent deletion. Silky’s Desert Racer, shown here, was their earlier vehicle, built entirely for speed, probably by Silky themselves. The chassis is retrofitted with an enhanced antigrav jet. The race was on, and the first merchant to a prize would get the information, so very little else was catered for in this cramped vehicle. It is this air of competition that drove the data merchants to almost legendary piratical status: Silky has one of the most storied careers, and was legendarily tough. Cross their path, and you may never live to tell the tale.

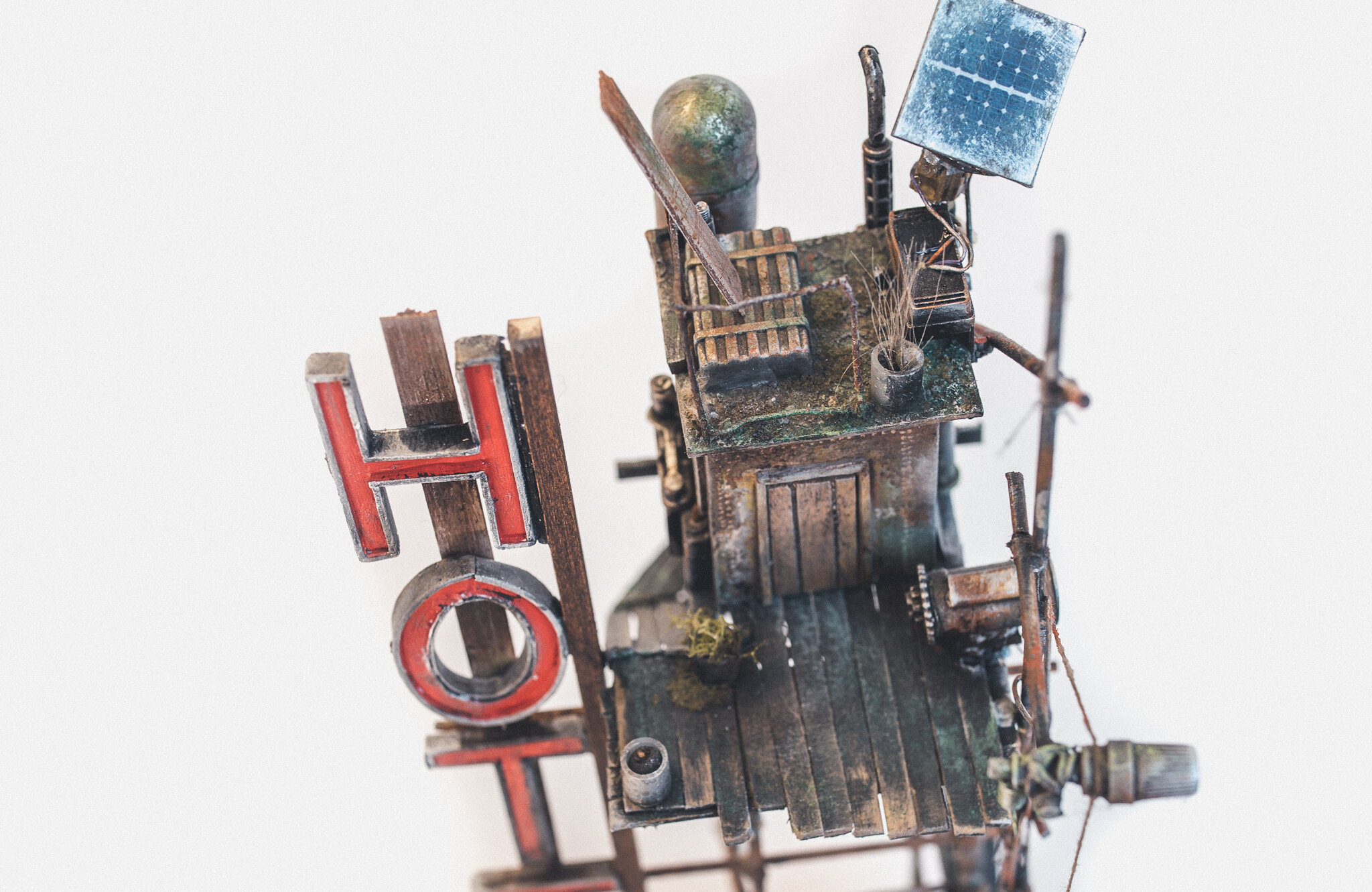

Stilt Dwelling, 150-250 PD

EXHIBIT 9: after the deluge, water levels rose worldwide to previous levels. populations which found themselves displaced quickly scrambled to construct dwellings in which to escape floodwaters. With swells reaching up to three or four metres in some places , it was essential to keep your habitat above water and with all the essentials for life at hand. Each dwelling could typically provide enough power for one or two occupants, though the speed at which they were built frequently put them at risk of collapse when the next big typhoon struck.

The Skimmer, 350-450 P.D.

Exhibit 47 shows a maquette of an algae skimmer, used for farming algae in the period 250-400 PD. We know from remaining climate data from the antedeluge period that the climate change experienced in the period led to blooms of algae levels in freshwater sources. During the period following the deluge, in which the population bottlenecked, a number of new food sources were looked to, as rising sea levels and desertification ruined previously ample agricultural land, now buried in sand and baked dry, or submerged under soupy, polluted water.

Use of algae as food was commonplace in this time, and formed the basis of our current usage of algae in the food stream. The maquette here shows a harvesting machine, part of a fleet owned by the East Plains Algae Harvesters Consortium. The Algae would be skimmed from the surface and sucked into the centrifugal separators, where the algae could be removed, and remaining water, mud and grit could be dumped out beneath the machine. The Algae would then be quickly processed on board and stored in tanks for later further processing. Algae was used for a number of other applications as well as a food crop, and the EPAHC grew wealthy selling their product for uses in fuels, fertilizer, and as a source of alginates. From what we know the algae processing did not render something too appetising, but enough to survive on with only some extra supplements.

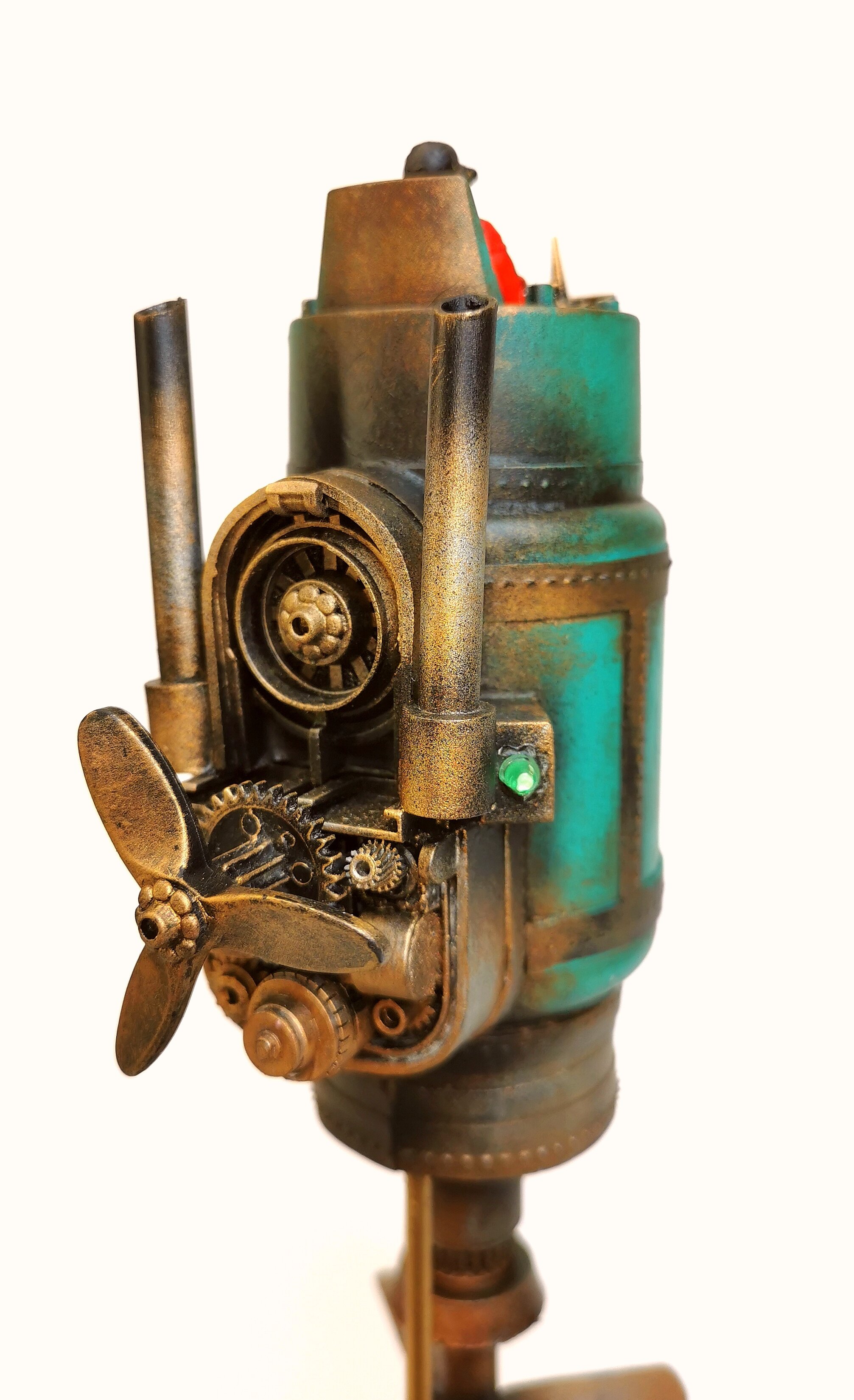

The flea, circa 150 P.D.

This maquette shows one of the earliest known prototypes for what would eventually become what we know as contemporary anti - gravity units, and existed briefly, more as a proof of concept. The science behind what we now recognise as Anti gravity technology had been understood for at least 50 years prior to this, but the complete collapse of infrastructure following the deluge made progress slow. The breakthrough came when new methods of feeding immense power into the cylindrical units was made possible through new fusion technologies, research that had begun pre-deluge, but which had been lost after that civilization crumbled.

Anti gravity units were paradoxically heavy, and this example here shows the main cylinder housing the rotating magnetic plates, atop a field generator. As the technology was proof of concept only, the actual propulsion was traditional; by means of rotors and blades, powered by regular combustible fuel. Though it only existed briefly, it's success was enough to push forward with further development, and allowed for wider conquest and exploration in the harsh environments. These units were to all intents and purposes a chair strapped to an engine, and It would probably have been quite uncomfortable due to the vibrations. It's unlikely that any of these went much further than the workshops in which they were created - it was however a key step to allowing anti grav tech to become available for everyone.

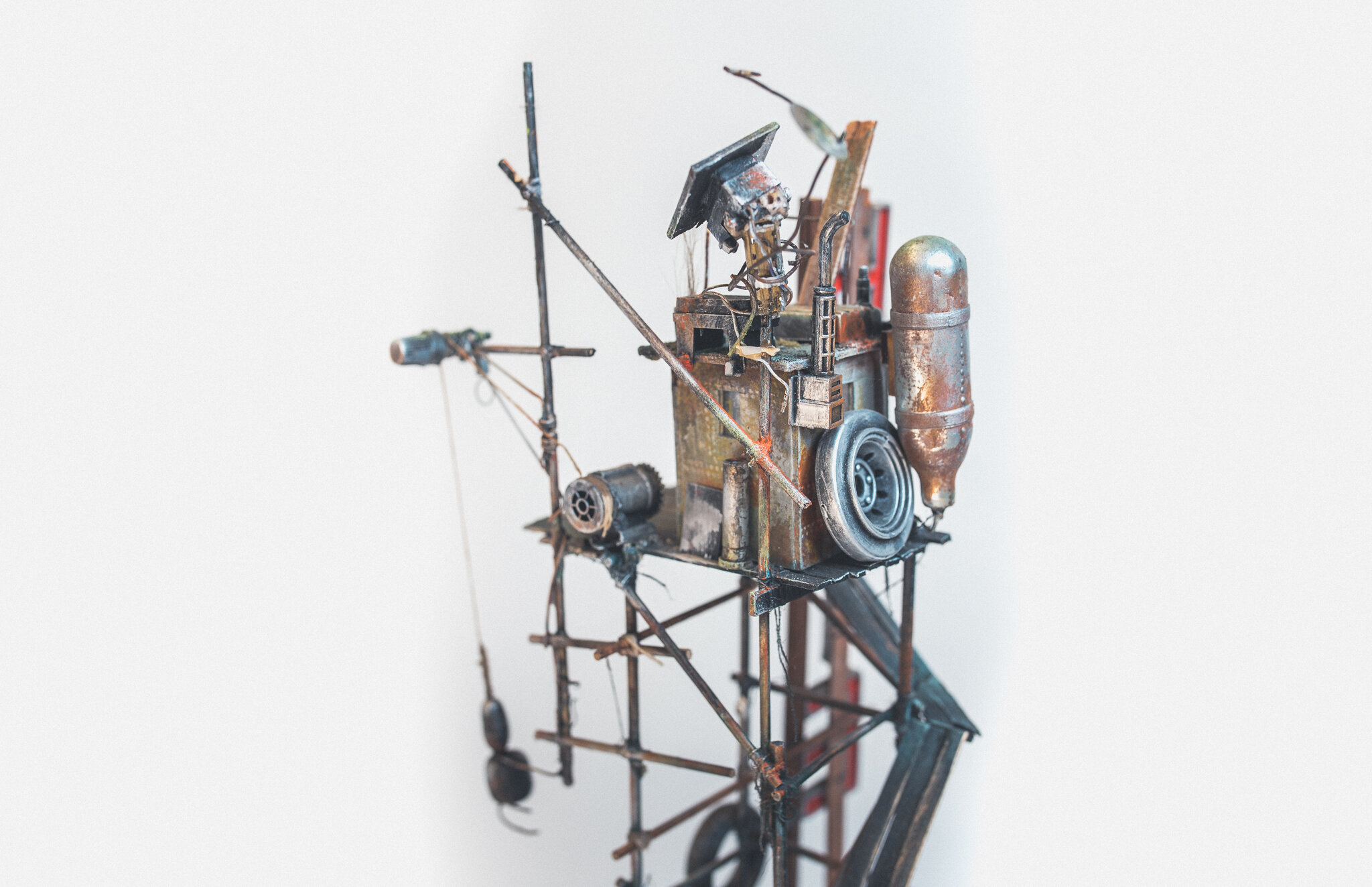

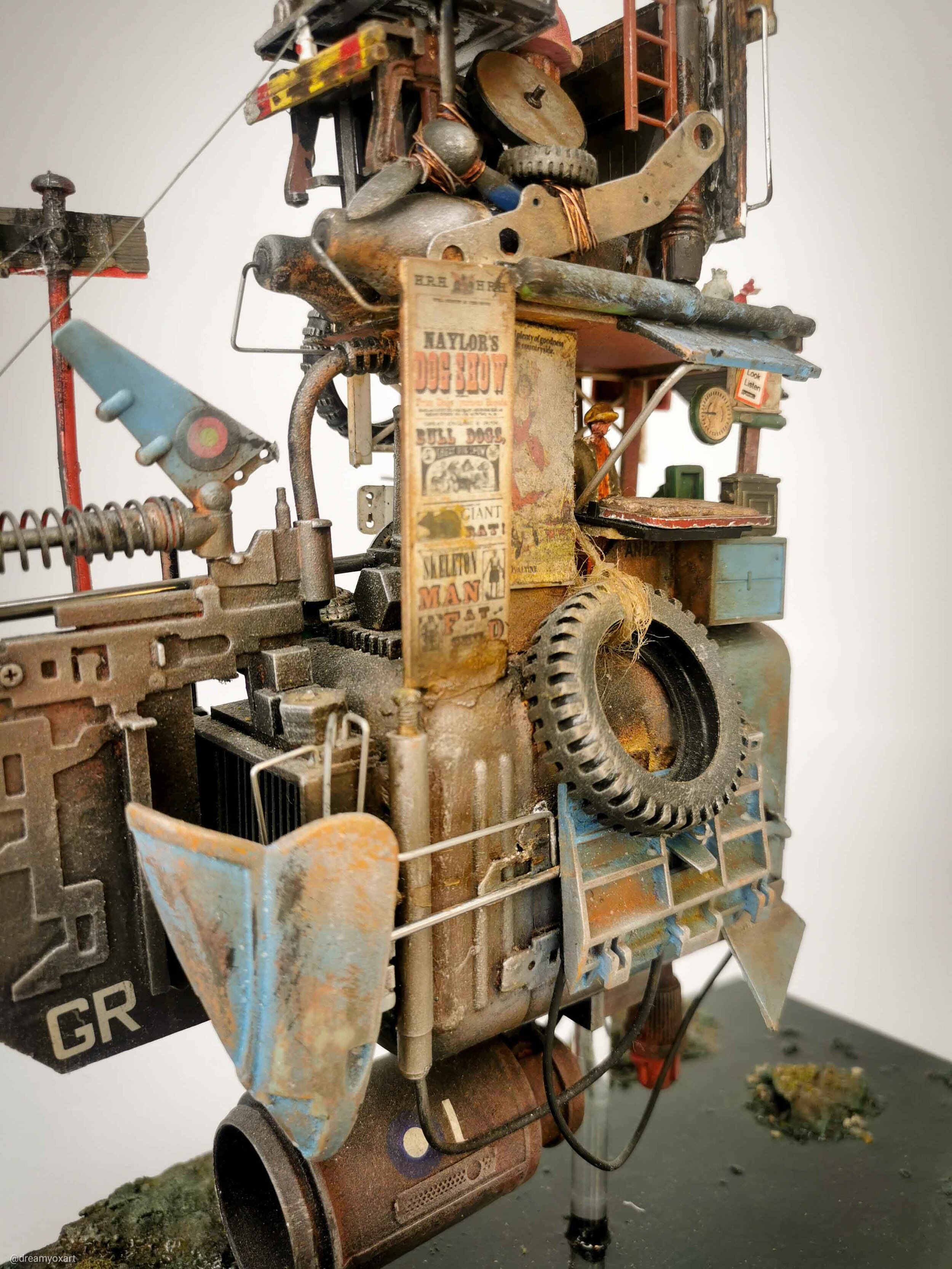

THE SCRAP MERCHANT: A BARTERING ECONOMY

MUSEUM OF THE ANTHROPOCENE EXHIBIT 17

Exhibit 17 shoes a maquette of a travelling scavengers vehicle, circa 250 - 350 P.D. Such vehicles were very common in the immediate post deluge period, and formed the background of numerous local economies across the world. The Ante Deluge period was ruled by financial services dealing in token based currency, and latterly, digital currency. Following the deluge, such economies collapsed entirely, and the earliest explorers of the new world found themselves dealing largely in a barter based economy, driven by those who could scavenge and supply whatsoever one might find themselves in need of. From vehicles like this one could easily source food, mechanical parts, flora and fauna, water and coolant, and a myriad of novelty scavenged items.

Vehicles such as this operated as sole traders or occasionally consortiums, with the ability to travel widely and maintain a wide base of customers essential. The vehicle was also fitted with powerful broadcast equipment, able to reach mid and long wave frequencies to maintain contact with all of them, allowing them to be called when needed. Traders such as this divided their time between scavenging and sourcing usable items from the ruins of Ante Deluge society, and travelling from dwelling to dwelling, trading what might be needed for whatever could be traded in return. With less room on deck, it was not uncommon to see these vehicles piled high with whatever they had found or traded. This particular model is based on the remains of a vessel from roughly 300 PD, discovered in 1780 PD on the south slopes of Mount Nairne.

MUSEUM OF THE ANTHROPOCENE 1898 P.D.

N.B. this model was damaged by someone in the museum last week. Could whomever is responsible take better care in future?

- The Curator

MONTY'S TUG:date unknown circa 250-800 p.d.

THis maquette shows a reconstruction of the tugboat known as ‘betty’.

An extract from Forrest’s Histories (1248 P.D.)

Monty didn't want to run a tug. To be honest he didn't want to do much. He had a small vessel, a place to be, and got by. When his first vessel was stolen, he had to wait until he could get another, which would only happen when he could scrape together enough to barter, or make do with what he found. He lived on the edge of the desert, and there were a fair few bits and pieces he could use. Plenty of vessels when crossing the desert were either broken down, lost, or occasionally, attacked and stripped for parts. Monty was pretty handy, and after a few months had enough components to start putting something together. He ended up with something he built around a rusted tug chassis that he retrofitted with a spare antigrav unit, and was able to trade a dealer for a couple of extra engines to help give it enough power to cross the essential weight/power ratio that anti-gravity generation required. He dubbed his new Frankensteins monster of a vehicle "Betty" after his aunt, and spent his time coming to aid of ships lost in the desert in need of a tow. With the extra power he had added, he could tow a vehicle three times his size, and his little shack on stilts at the edge of the desert with Betty parked alongside became a regular sight for those crossing the plain. Monty was happy enough. He didn't have to work much, and besides which, there was enough business to keep him in food and drink. He lost Betty in a bet a few years later, and she was last seen running illicit imports between settlements.

AFTER THE DELUGE

A NOTE FROM THE CURATOR

Human life on planet earth has always been one that has existed by the whims of nature only. The conditions that allowed life to flourish and evolve were seemingly serendipitous, as were the conditions that allowed such a creature as a human to come into being. Mankind, from it’s first origins 6 million years ago has existed for a mere 0.13% of the planets 4.5 billion year life span. And yet, in the last 4000 years, mankind found itself in a position never witnessed before. The age of the Anthropocene defines the period in which Humanity affected the climate, to such and extent that it ultimately brought itself to both the peak of it’s technological inquisitiveness and excellence, and lost it all through a combination of greed, hubris, and lack of forethought.

At least this is what we are commonly taught. And while it is true, that by the time the devastating effects of climate change were known, the steps taken to prevent the catastrophic loss of life and society were not taken readily enough, new evidence and study of the era has shed new light onto this murky era. The advent of industrialisation permitted a society that at its peak, was able to send humans to space, create ever more fast and advanced land, sea and air vehicles, and an advent of computerisation that was on the cusp artificial intelligence. By the time it was clear that the efforts to stop the process were too late, much of mankind was agreed and aware of the risks that the pollution of 300 years had wrought. However, easy as it is to see these people as hubristic, callous, or deluded, we posit that these people were victims of a system that was not engineered or possible for most to take the action needed. In human history, various empires and civilisations rose and fell; The Achaemenid Empire, Assyrian, Roman, Kushite and Carthaginian, among many others. The Ante Deluge Empires, concentrated in what appeared to be wealthy and prosperous nations, fell like many others had before it. But the damage wrought by the affects of industrialisation, a booming population that at it’s height we believe may have exceeded a world population of over 8 Billion, a figure we still are far from reaching nearly two millenia later, we now know changed the planet in extraordinary ways.

In the intervening 1800 years, the incredible loss of life, combined with slow and steady research and development, a loss of ancient land borders and empire lines, and a shared commonality to a higher goal, has allowed us to develop the society we have today. The Deluge, (the day on which it is commonly accepted that all previous notions of society finally collapsed in the face of extreme weather, destruction that saw populations collapse by over 85%, and destroyed vast tracts of previously inhabitable land) was arguably a turning point for mankind. The great reset of this time is incalculable, and we lost so much data on this era, that the following years of darkness meant old calendars were abandoned for the markers of this turning point; Ante Deluge and Post Deluge society.

The years following The Deluge are seen as a new “Dark Ages” of sorts, one in which man struggled to survive, and did so by only a hairs breadth. However, it also forged the ground for some of the technological advances that led to our society as we know it now. The advent of Anti-Grav technology, completely non-polluting everlasting fusion power, increasing miniaturisation, all were developed during this period. It may have taken mankind the better part of 1800 years to reach the place we are today, but we owe these early pioneers, who were dealing with large scale destruction on a scale never seen before.

This exhibition, made up of artistic representations for how we think these people lived and travelled, aims to shed new life on this period. Please enjoy.

THE CURATOR, 1898 P.D.

Artists impression